For this article, we interviewed a wide variety of students, teachers and administrators to get their insights on the effects of COVID-19 on higher education in the U.S. For the broad purposes of this article, we use higher education and post-secondary education to refer to colleges (community colleges, technical schools and liberal arts colleges) and universities (public and private institutions that offer both undergraduate and graduate programs).

In 2019, college and university classes were utterly saturated with students, and enrollment at degree-granting post-secondary institutions was just 7 percent less than its all-time 2010 peak of 21 million students. However, in early 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic caused unprecedented disruptions to higher education. Educators, much like everyone else, found themselves scrambling. In a very short period of time, campuses were closed, social activities were curtailed and university life as we knew it ceased to be.

After two difficult years of living in a global pandemic, we’ve come to understand that COVID-19 is not going away. Many students are back on campus and everyone from parents to administrators are desperate for a return to normalcy. However, it is a “new normal” that colleges and universities must now navigate, and just like the coronavirus itself, the changes that have occurred at institutions of higher learning are not going away anytime soon.

College Goes Online

In the fall of 2019, 19.6 million students enrolled in colleges and universities in the U.S. Of those students, 63 percent (12.3 million) took no distance learning courses. The remaining 37 percent (7.3 million students) attended at least one distance learning class, and 17.6 percent (2.4 million students) exclusively took distance learning classes.

In the spring of 2020, more than 1,300 colleges and universities in all 50 states canceled in-person classes or shifted to online-only instruction. While online classes proved to be a lifeline for some, it proved to be a hurdle for others. According to the Economic Policy Institute, “Research regarding online learning and teaching shows that they are effective only if students have consistent access to the internet and computers and if teachers have received targeted training and supports for online instruction.”

While many students and professors enjoyed going online and would prefer to stay there at least part of the time going forward, there were certain college experiences that simply could not be replicated during online learning.

Students who had looked forward to study abroad programs found that their programs were cut short or canceled altogether. Data released from the U.S. Department of State and the Institute of International Education showed that there was a 53% drop in students studying abroad during the 2019 to 2020 academic year, which included the summer of 2020.

The Digital Divide

When colleges and universities went online, it had the unintended consequence of widening the digital divide. A report done by the Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights, found that the pre-existing educational gaps in access, opportunities, achievement and outcomes only widened during the last two years. Low-income students and students of color enrolled in lower numbers and dropped out in higher numbers.

The National Student Clearinghouse Research Center found that among students from low-income high schools, enrollment to four-year colleges dropped 29 percent and enrollment to community colleges dropped 37 percent. A study done by the U.S. Census Bureau in August of 2020 found that students from families making less than $75,000 a year were nearly twice as likely as students from families who made over $100,000 a year to report that they canceled their plans to take college classes.

The reliance on technology gravely affected those who didn’t have access to high-speed internet or computers. Students who serve as caregivers to young children and elderly relatives found themselves prioritizing rent payments and childcare over upgrading their technology. Students with disabilities also found themselves without the support and resources they needed to access education remotely.

Online and hybrid learning will undoubtedly continue with or without COVID-19, which means that bridging the digital divide and bringing equity to online education is an immediate and paramount concern for all institutions of higher learning. With the right tools and technology in place, distance learning has the potential to benefit the same populations that were disadvantaged by it during the pandemic.

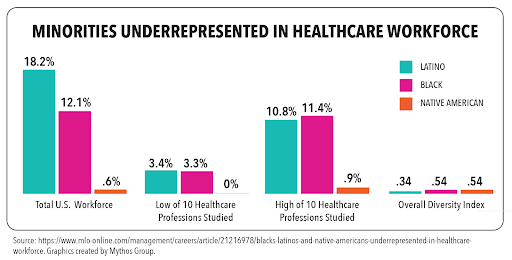

Specific fields of study that are lacking in diversity have the greatest opportunity to increase enrollment of minorities and marginalized students. For instance, a 2019 study done by researchers at George Washington University looked at data from the American Community Survey and the Integrated Post-Secondary Education Data Systems in order to develop a health workforce diversity index.

According to the researchers, a diversity index of 1 would mean that the diversity of the workforce was equal to the diversity of employees in one of 10 healthcare professions studied. However, what they found was great disparity for Latino, Black and Native American populations.

As we saw during the pandemic, Black/African American, Hispanic/Latino, American Indian and Alaska Native persons experienced higher rates of COVID-19-related hospitalization and death compared with non-Hispanic White populations. According to the Focus for Health Foundation, it’s reasonable to assume that recruiting more minority students into health-related fields will result in better health outcomes and greater healthcare equity for underserved communities.

Goodbye Standardized Testing

To combat decreased enrollment numbers, colleges and universities altered their admissions policies to reduce barriers to entry. A noteworthy change was making standardized testing an optional factor in college admissions. Pre-pandemic, 1,070 schools were test optional. In the fall of 2022, more than 1,815 colleges and universities suspended their requirements for American College Test (ACT) or Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT) scores. A full list of these colleges and universities reveals that virtually all well-known institutions of higher learning have currently adopted this policy.

Standardized testing has long been a source of controversy, with critics arguing that it favors students of means who are privileged enough to hire expensive tutors for extensive test prep. In an interview with Smithsonian Magazine, Laura Kazan, a college advisor in Acton, California noted, “If you want to know where people’s zip codes are, use the SAT.” Even the brightest students often do poorly on their ACTs or SATs if they haven’t learned the proper test-taking skills.

For decades, these high-pressure tests have been dreaded by parents, teachers and students. As more and more colleges and universities assemble classes without the “benefit” of standardized tests, it’s increasingly likely that they will be proven to be unnecessary. COVID-19 has forced us to reassess so many aspects of our lives, and it’s possible that the standardized testing requirements for college admissions will not survive the reexamination.

A New Value Model

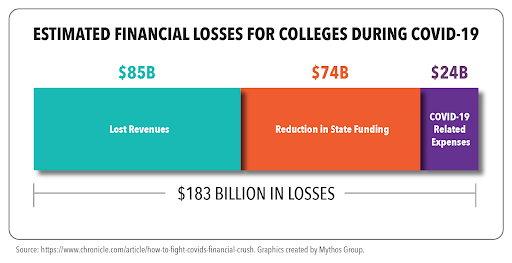

According to The Chronicle of Higher Education, COVID-19 has caused colleges and universities to lose an estimated $183 billion dollars – the largest financial loss that the sector has ever experienced. Reduced enrollment, tuition freezes, suspended or shortened study abroad programs and continuing pandemic-related expenses have all contributed to this historic loss. In addition, state-run institutions are seeing a reduction in higher education funding.

In order to survive the seismic shifts that COVID-19 has caused, post-secondary schools are likely to change to a more value-based approach that embraces nontraditional forms of learning. In an Inside Higher Ed article, authors Arthur Levine, a distinguished scholar of higher education at New York University’s Steinhardt Institute for Higher Education Policy, and Scott Van Pelt, the Associate Director of the Wharton Graduate Communication Program, discuss this new model.

According to them, knowledge institutions of all kinds, including colleges and universities, are increasingly adapting by “rejecting time- and place-based education, creating low-cost degrees, adopting competency- or outcome-based education, emphasizing digital technologies, focusing on the growing populations underrepresented in traditional higher education, and offering pioneering subject matters and certifications.”

If we read between the lines here, this is what we find – traditional and nontraditional students are looking for education alternatives that give them more value. These alternatives tend to be specialized programs that offer their education product in a way that takes less time, costs less money, is more accessible, and provides an overall better bang for their buck.

Programs that give students the exact skills they need to get a desired job are often going to be more attractive to students than a traditional four-year institution that may leave them with decades of debt and no guarantee of a job at the end. Colleges and universities who don’t adopt options for upskilling, reskilling, just-in-time learning, or need-based training will continue to find themselves in a precarious position.

Student Health And Mental Wellness

Student health and safety has always been a priority for universities, but COVID-19 threatened the environments that most administrations had always thought to be safe. Crowded living in dorms, social activities, class size and virtually every other aspect of on-campus life took on an element of danger. As we’ve noted, in the early days of the pandemic, the first line of defense for most schools was to send everyone home and conduct classes online.

Once students started trickling back onto campuses, other measures were taken such as mask mandates, reduced class sizes, sanitizing stations and eventually vaccine requirements. The success or failure of these mitigation strategies is not well known. States largely made up their own mandates which resulted in a patchwork of regulations whose enforcement was spotty at best.

To complicate matters, many of the measures taken to protect students and faculty from the coronavirus ended up triggering a mental health crisis. According to a study done by NCBI, 71 percent of the college students interviewed reported increased feelings of stress and anxiety due to the COVID-19 outbreak. Students worried about their health and the health of their loved ones. They had difficulty concentrating, problems sleeping and increased worries about their academic performance.

Over and over again, we heard from students that the one thing they missed the most about classes going online was the loss of social interaction. This isolation and loneliness were experienced across the board no matter the major, year or institution and was observed by students, parents and teachers alike.

COVID-19 has inflicted trauma on a global scale. At this moment in time, the physical dangers of the novel coronavirus are diminishing. But even as the physical dangers of the coronavirus diminish, the mental and emotional dangers will linger and perhaps increase. The understanding of what it means to keep students healthy has changed, and campuses will need to make adjustments to their student healthcare and emergency plans in order to keep students truly safe and well.

How Colleges Can Adapt

Part of the reality of this pandemic is that the situation is fluid. At the time of this writing, China has ordered 51 million people into lockdown as COVID-19 surges there. The CDC has reported an uptick of the novel coronavirus in wastewater samples across the U.S. The calculus changes every day, and the threat of continuing surges is real. While we cannot fully know or eliminate the risks we might face in the future, we can adapt in order to overcome some of their challenges.

As the pandemic continues to evolve, many students are choosing to take a gap year, attend college part-time, or stay closer to home. To combat the threat of declining enrollment, we recommend that colleges and universities do the following:

- Offer permanent distance learning options. During the pandemic, many employees found that they preferred working from home as opposed to going into an office every day. Similarly, many college students and faculty found that they preferred to learn and teach from home as well. Organizations should invest in the technology and training necessary to make online and hybrid-learning models a permanent part of their course offerings for those who prefer them.

- Start early to build long-term trust. Creating long-term trust can only be done by recognizing the uniqueness of each individual’s situation. Universities can offer personalized resources which may focus on mental health, financial need, family situation or any other specific barrier to entry.

- Commit to diversity, equity, inclusion and belonging. Institutions of higher learning will do a great disservice to themselves and to society as a whole if they don’t actively work to bring back the marginalized students who dropped out or failed to enroll during the pandemic. Recruitment resources need to focus on disadvantaged schools in low-income districts and find ways to bring these students back into the fold.

- Refine tuition pricing models. Regarding the financial loss associated with post-pandemic higher education, we recommend that colleges and universities reevaluate their financial goals and strategies. For example, in such unprecedented times, they might consider widening their acceptance margins. As mentioned above, colleges and universities can adopt an individualized approach to pricing models. This could look like offering personalized financial aid packages or implementing an optional pricing structure that considers the uncertainty of the future.

- Develop new educational models. There has never been a more opportune time to “think outside of the box” when it comes to higher education. In a post-pandemic world, students may be seeking alternatives to a traditional four-year education. Offering certificate programs, specialized training, reskilling and upskilling tracts or reduced-tuition models may attract many students who would otherwise seek this kind of instruction elsewhere.

- Support student health and mental wellness. We recommend creating a robust on-campus student health center where students can receive primary care and mental health services. The student health center should also serve as a one-stop shop for vaccinations, treatments, contact tracing, personal protective equipment (PPE) and counseling. Having on-campus housing where students could quarantine and attend school online may also be necessary in the event of continuing COVID-19 surges or future pandemics.

- Offer a safety net. Colleges and universities need to closely monitor at-risk students and offer support services to keep these students enrolled. Early interventions can reduce mental health issues like feelings of loneliness, isolation, depression and anxiety as well as identify external stressors that may keep a student from achieving their academic goals.

At Mythos Group, we work with private-sector, public-sector and academic institutions to identify and eliminate pandemic-related pain points. If your organization needs help crafting a successful post-pandemic roadmap, please visit our website to learn more about what we do.

Our team of transformation specialists are experts at solving the most complex strategic and organizational challenges so that you can develop innovative solutions that propel your institution ahead of the competitive curve. We’d be honored to work with you.